Payrolls: Warning Signs

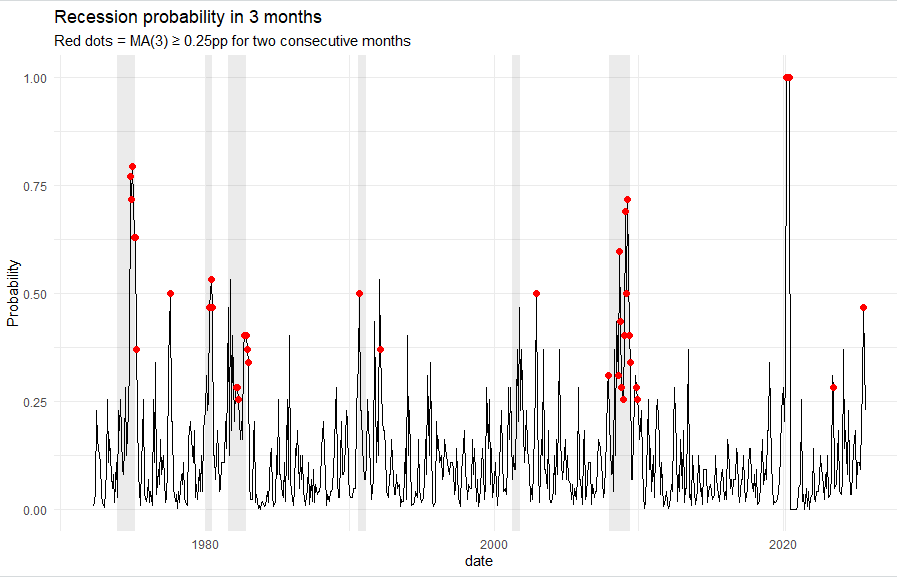

Today's labor market data could well be poor according to three signals, especially the unemployment rate. My model predicts a half point rise in aggregate unemployment over the next six months

Labor market change happens first at the margin. It is employees with short tenure, in cyclical industries, and with fewer internal labor-market connections who are the last to be hired in an expansion and the first to be fired. Often, those workers are African Americans. Ahead of today’s labor market data, I focus on movements in Black unemployment and the broader labor market, temporary help employment, and Jerome Powell’s press conference comments on the volatility and unreliability of the household data.

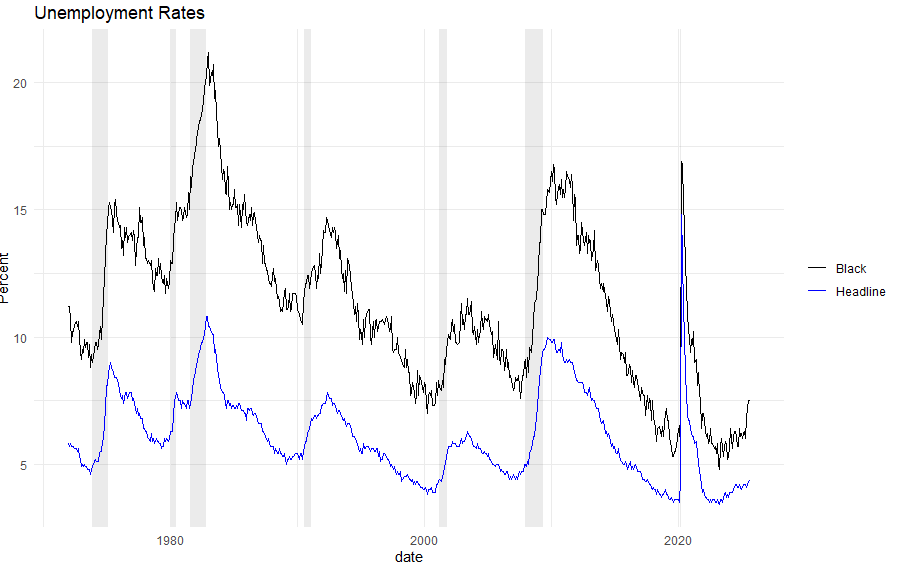

Black Unemployment as a Leading Indicator of the Wider Labor Market

Labor market downturns affectmarginal workers first, who are often African Americans. They are disproportionately affected by hiring downturns and then by the early stages of layoffs.

The data we have up until September shows a significant rise in the unemployment rate of African Americans, from an average of 6.1 per cent in the first five months of the year to 7.4 per cent in the latest three. The unemployment rate of African Americans is noisy, but often contains a signal about the trend in verall employment.

When I used the series with various smoothing techniques to predict the probability of recessions, the noise in the series led to too many false positives to make it reliable. However, the recent readings are an amber warning.

I explored the extent to which Black unemployment helps predict the wider unemployment rate. I used a model that starts with an estimate of the trend in Black unemployment, predicts the next period's outcome, and then updates its estimate of the trend based on the forecast error (the Kalman filter local-level model). It’s a way of smoothing the data that helps separate the trend from innovations in the data.

Once Black unemployment is decomposed into a structural level and unexpected shocks, the shocks—not the trend—provide a clean early signal of labor-market deterioration. We are looking for clusters of shocks that indicate an increasing deviation from the previous trend, as we see in the inherent data.

When I regress changes in the aggregate unemployment rate on innovations in African American unemployment rates, the cumulative shock to African American unemployment over recent months implies roughly a half-percentage-point rise in the aggregate unemployment rate over the next six months — a meaningful deterioration signal, even as the most recent monthly surprise has faded.

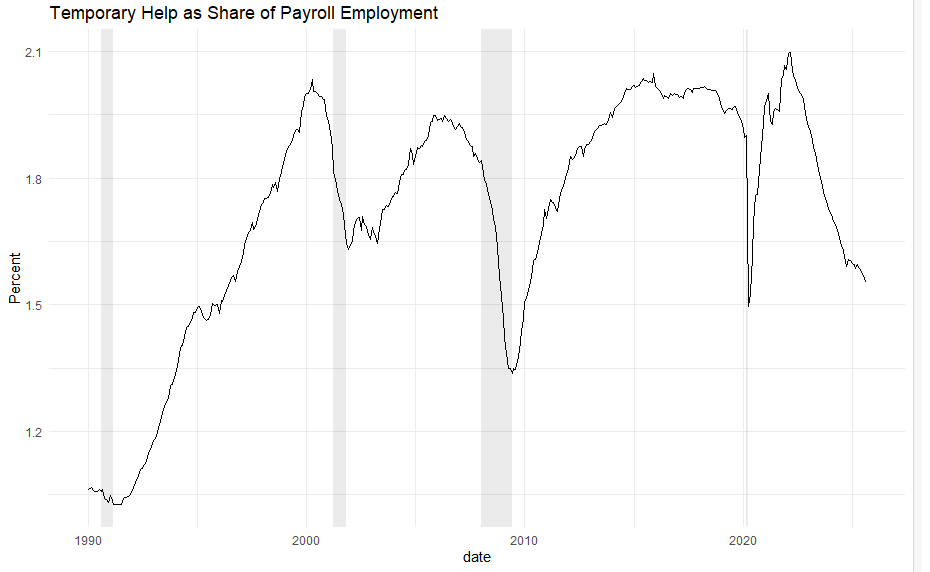

Temporary workers take a tumble

Another group of workers on the margins of the labor market are temporary workers, who are easyto let go when demand turns down. The share of temporary workers in the labor force, shown in the chart as a percentage, is now at levels seen in previous recessions. However, many unauthorized immigrants work, often in demanding, low-wage sectors like agriculture, construction, and food service, filling roles that can be seasonal or temporary, which may depress the share. Thus, the immigration crackdown could have exaggerated the fall in temporary workers. Nonetheless, recent numbers have not seen an increase in the previous rate of decline, so it is again a warning sign of possible bad news to come on payrolls and unemployment.

Powell warns of higher unemployment

In my preview of the last FOMC, I said two things would worry the Committee: the first, signs of money-market stress; the second, concerns about the labor market. I predicted that some of the hawks on the FOMC would likely change their views from October on the desirability of a cut in December. The Fed did cut rates, and took measures to calm money markets.

In terms of labor markets, the tone of Powell’s press conference was more dovish than in October, despite delays in official data. Some series, such as Challenger layoffs, pointed to a deteriorating labor market. The Chair said that recent payroll numbers were overstated and that the true trend was a fall of around 20,000 a month. I also wonder whether the Fed may have been hinting at what the delayed data will show, since layoffs will likely boost unemployment during the shutdown. That would help explain Chair Powell’s comment that household data may be volatile and unreliable when released. Prepare for a bad number that the market will struggle to disentangle the signal from the noise.